The Continental Divide Trail (CDT) spans approximately 3,100 miles from Mexico to Canada and is one of the most significant trail systems in the world. It’s the most remote, and, in many ways, most challenging of America’s long-distance National Scenic Trails. Thru-hiking the CDT is an adventure of a lifetime, but it’s not for the faint of heart. That said, the effort it takes to overcome the challenges of the CDT is rewarded with unending panoramic views, deep solitude, and an opportunity to be immersed in true wildness.

Successful long-distance hikes begin at home with extensive research, careful planning, and strong commitment. To help you get started on this journey, we’ve created this guide. It includes tips on selecting a start date, purchasing gear, understanding what to expect on the trail, and much more.

Thru-Hiking The Continental Divide

Each year, a few hundred people attempt to thru-hike the CDT, and not all finish. Unlike other long-distance trails, like the Appalachian Trail or the Pacific Crest Trail, there are lots of alternative routes on the Continental Divide Trail.

The resources we recommend below tell you what you need to know about the most popular routes. They are all scenic, remote, and challenging. Your route choice may depend on weather, resupply needs, fires, trail closures, floods, or wanting to see certain landmarks.

CDT By The Numbers

- 2,700-3,100 – Approximate length in miles depending on the route chosen

- 5 – Number of states the CDT traverses

- 150 – Average number of days it takes to complete a CDT thru-hike

- 24 – Average daily mileage

- 457,000 – Approximate elevation gain and loss in feet of the CDT

- 14,278 – Highest point in feet (Gray’s Peak, CO)

- 4,200 – Lowest point in feet (Waterton Lake, Alberta)

- $5000-$8000 – Average on-trail expenses

- 4-5 – Average pairs of shoes a CDT hiker will go through

What to Expect on A CDT Thru-Hike

Thru-hiking the CDT is incredibly fun, exciting, and awe-inspiring, but it definitely has some specific challenges. It’s not recommended as a first thru-hike unless you have considerable backpacking experience. Ideally, you’ll have already hiked a long-distance trail with similar challenges, like the Pacific Crest Trail, and you should know how to read a map, use a compass, manage resupplies, and deal with limited water. That said, anyone who does their homework and is determined enough can be successful. No matter your experience level, you might enjoy our article on tips for the first time thru-hiker – it’s packed with good information to help prepare you for a long-distance hike. Here are some common things you’re likely to experience while hiking the CDT:

Solitude

Compared to the Appalachian Trail or Pacific Crest Trail, a relatively small number of people attempt to thru-hike the CDT each year. Its popularity is growing, but the reality is you might not encounter any other backpackers on some stretches. It’s important to be self-sufficient and comfortable with limited social interaction. Lots of hikers combat loneliness with a project (keeping a journal or making videos), reading, and listening to music or podcasts. Solitude can be a beautiful thing. Just make sure to take care of your mental health, visit friends or family if you have the time to hop off the route, try to plan for friends or family to meet you for some stretches, have a solid logistical plan, and stay on your toes out there.

Big water carries & dry camping

Water availability on the CDT fluctuates drastically based on your start date, snowpack, and the weather. Generally, sources are far apart and unreliable in the desert. Water can also be inaccessible in the mountains when the trail stays on ridges for long periods. We had to “camel up” and carry six liters of water to make it 20+ miles between sources on many occasions. Lightweight foldable bladders, like Platy Bottles, come in handy for big water carries. The best advice is to stock up wherever you can, never leave a source thirsty, and carry more than you think you need. There’s no guarantee you’ll find water in a source when you get there. The CDT water report is a crowd-sourced resource that can be very helpful. Here are some tips for finding water on the CDT.

Questionable water sources

CDT hikers should be equipped with a water treatment method that can handle heavily contaminated water. For a good portion of the trail, stock tanks are the main watering holes for both backpackers and livestock. Be mentally prepared to drink from mud puddles full of cow poop to stay hydrated. It’s also common to find dead mice and lizards in CDT water sources (they were thirsty too). It’s part of the adventure! It’s always a good idea to carry a backup treatment, like chlorine dioxide pills, since filters can clog and electronics on UV purifiers can fail. It’s all too easy to pick up a nasty intestinal parasite, like giardia while thru-hiking the CDT if you’re not on your A-game. We recommend carrying flavored drink packets or hydration tablets to make funky-smelling water palatable.

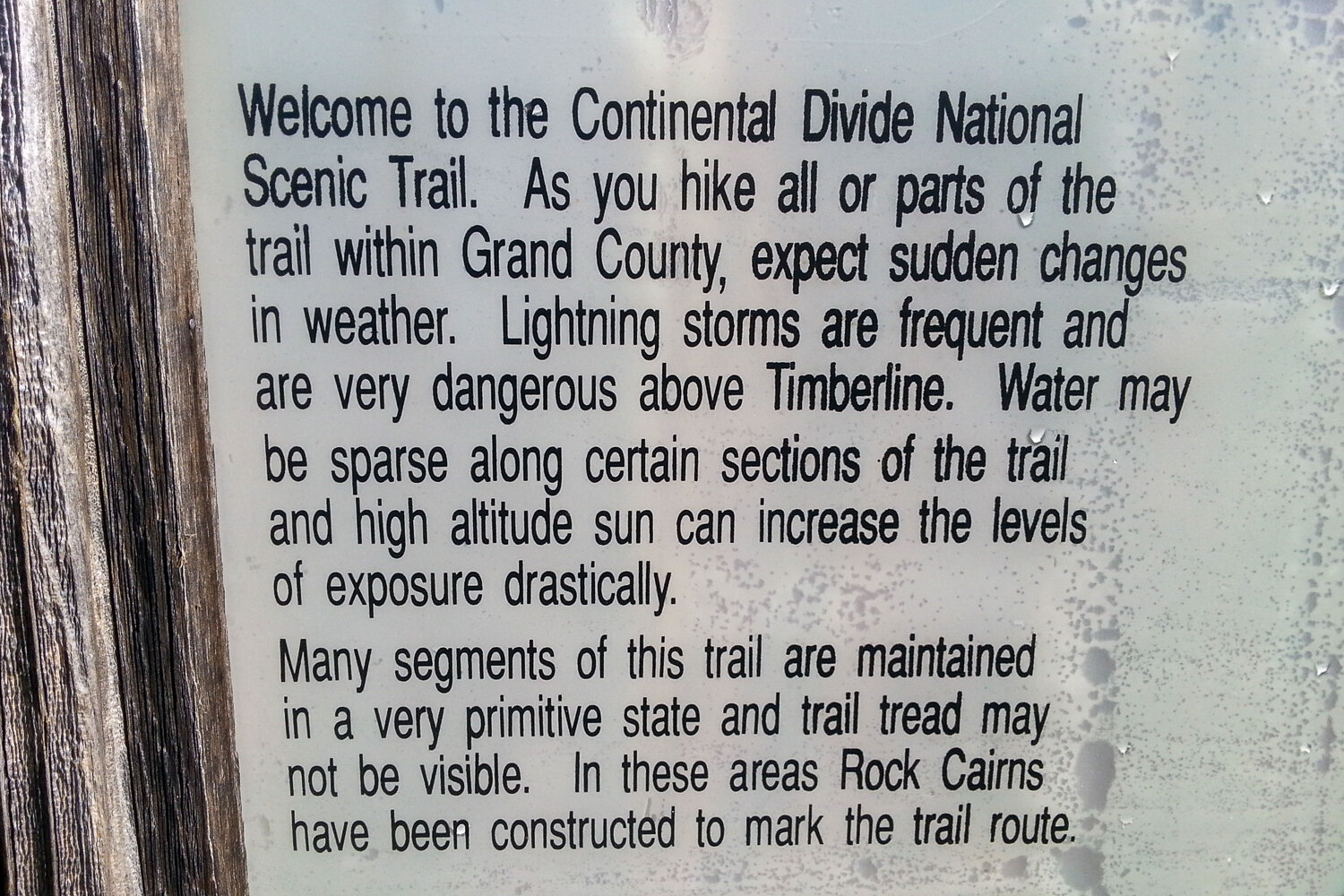

Storms & big temperature swings

Weather is at the top of the list of reasons why thru-hikers might need to call it quits and try again another year or complete a skipped section the following season. Strong UV radiation (all that high-altitude hiking), fast-moving weather systems, wildfires and their unrelenting smoke, and snow can beat down even the best thru-hiker.

The CDT passes through a diverse gamut of climates from hot, dry deserts to cold, alpine tundra. Desert temps can fluctuate by as much as 60 degrees from daytime to nighttime. You might need to seek shade and rest during the heat of the day, then contend with freezing temps soon after the sun goes down. The weather also changes very quickly in the Rockies, and CDT hikers should expect frequent storms. Spring and summer are monsoon seasons in the southern states, and torrential rain, hail, and lightning can happen anytime. Be ready for anything, even if the forecast calls for good weather. To us, the rapidly changing weather was exciting, but we were really glad to have our warm down jackets and solid rain gear (including umbrellas).

Snow travel

Snow travel requires excellent navigation skills and a bit of extra gear, including an ice axe, snowshoes, and/or microspikes. It burns a ton of calories, too, so make sure you plan for a raging metabolism (aka hiker hunger). Whichever direction you hike, you’ll encounter some steep slopes, avalanche terrain, and unstable snowpacks. Check out our video tutorial, Crossing Snow and Ice Axe Self-Arrest.

Navigation challenges & tools

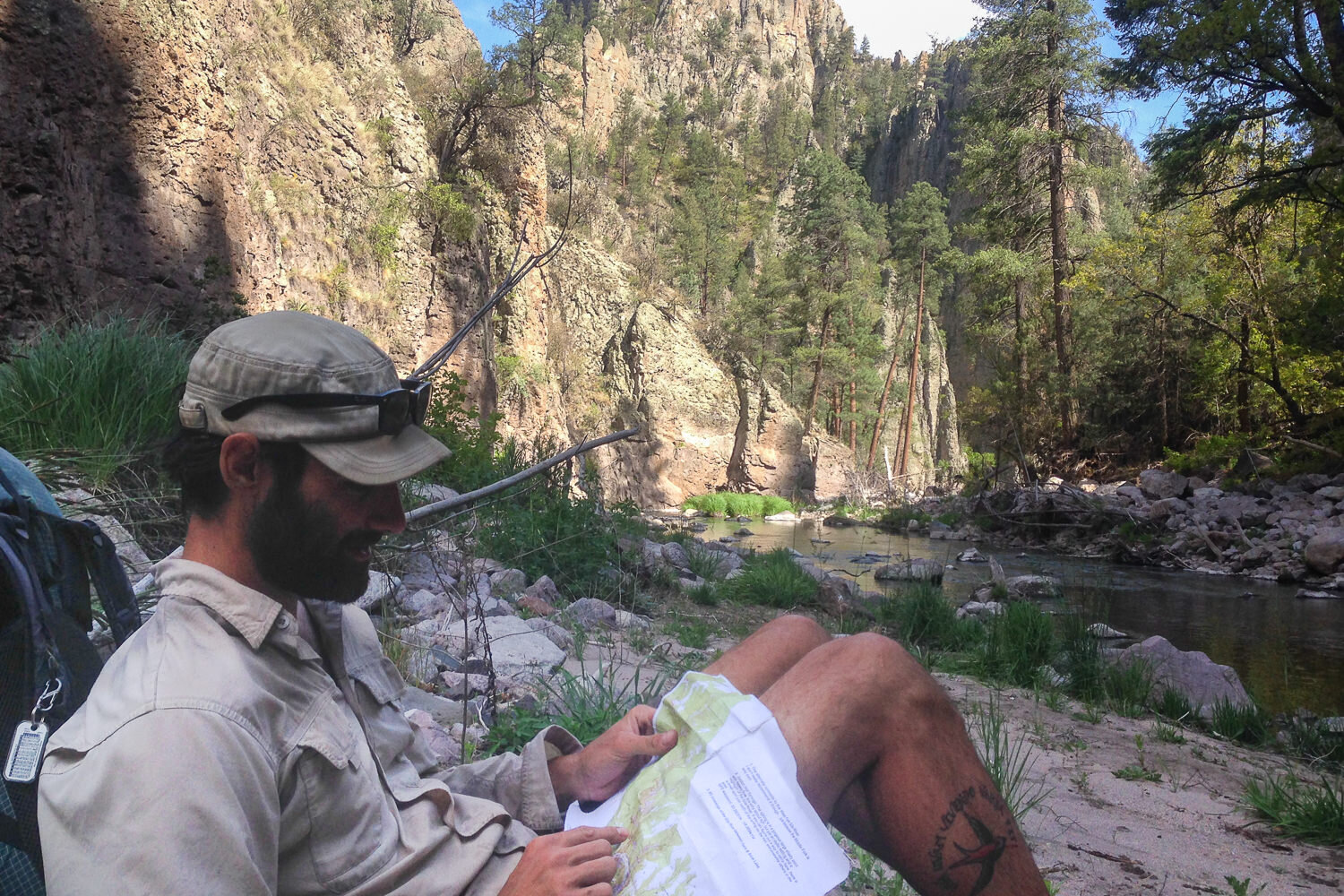

Navigating your Continental Divide Trail thru-hike is a process that is unique to every CDT thru-hiker because of how many alternative routes, trail changes/closures, and options there are. It is also why someone who completes the CDT might do it in 2800, 3000, or 3100 miles. Although there’s a lot more trail signage now than there used to be on many parts of the CDT, the frequency and appearance of blazes are very inconsistent. Because of this, you’ll have to pay pretty close attention to your maps or GPS to avoid getting off track. CDT thru-hikers should be confident in their way-finding skills; it’s common to use a combination of maps like Bear Creek Survey maps (or even two sets of maps like Jonathan Ley’s) with a compass, GPS, and a smartphone with a navigation app for redundancy. This may seem like overkill, but each tool has its advantages and disadvantages, so they will all come in handy at different times. You’ll be happy you have them when you need them.

High altitude

There are long stretches of the CDT that stay above 10,000 feet in Colorado, which means you’ll have epic panoramic views for weeks. Unfortunately, the sustained high altitude also means Acute Mountain Sickness – commonly known as altitude sickness or AMS – can be an issue. It’s common to feel more tired than usual, have a mild headache, or feel like you need to breathe deeper to fill your lungs at these heights. See our guide on how to train for hiking & backpacking trips for more tips for high-altitude hiking success.

Hitchhiking

Hitchhiking is part of the adventure for most CDT thru-hikers since many of the towns used for resupply are a very long way from trailheads or highway crossings. Most residents of resupply towns know when it is hiking season and are happy to be part of your journey. We’ve accepted many rides from strangers over multiple thru-hikes and have seen a lot of good in people. We’re really grateful for our positive experiences with hitchhiking, but we definitely recommend being cautious. When hitchhiking, start early and prioritize safety. Trust your instincts – if a ride feels unsafe, politely decline using any excuse. Stay alert, and whenever possible, travel with a companion to reduce risks. Many of the topics above are covered in more detail in our guide, 20 Tips for Backpacking in the Desert.

Planning

Good planning starts with the right resources. We’ll send you in the right direction to the most popular books, maps, websites, and tools below. We’ll also walk you through the basics of choosing a direction and start date, getting permits, and more.

MAPS & RESOURCES

Most hikers use the following resources to plan their hikes:

- CDTC website (free planning guide, southern terminus shuttle, water report, current conditions/closures, stewardship, and education)

- Yogi’s Continental Divide Trail Handbook (trail town maps and amenities details, resupply addresses, and alternate route info.)

- Walking with Wired’s tutorial on how to load POIs/waypoints onto a GPS.

Most popular maps/navigation tools (we used all of these on our CDT thru-hike):

- Jonathan Ley’s Maps is a great free map collection with cliff notes produced by a legendary CDT hiker. (Side note: You can get his take on the CDT’s flavor by reading some highlights of his trail notes on the storytelling and climate action site Hike the Divide.) Jonathan Ley’s maps are also available for offline use through the Avenza Maps App.

- Bear Creek Survey/CDTC Maps (these two map sets use the same info)

- FarOut Guides CDT Phone App (tracks progress on map, shows elevation profiles, water sources, etc.)

- Bear Creek Survey GPS Waypoints and Data (a GPS with waypoints is very helpful in the snow and is more reliable than a phone with an app)

Choosing a direction

Choosing which direction to take really depends on your style, schedule, and what you want to get out of the hike. Most people hike northbound (NOBO) on the CDT, but southbound (SOBO) is gaining popularity. Here are some things to consider when making your decision.

NOBO

- Pros: Can be more social/less solitary, overall temps are generally warmer, NM is a good warm-up for harder terrain up north, hiking CO in wildflower season, ending in Glacier NP feels more epic

- Cons: Heat in Southern NM, summer thunderstorms in CO (June/July), pressure to reach Glacier NP before snow begins in fall, can be less solitary/more social

SOBO

- Pros: There’s less rush to finish, aspens turning gold in CO, avoid thunderstorms in CO, more solitary/less social, hiking MT in wildflower season, cooler temps in NM

- Cons: Decreasing daylight every day, the trail is difficult right out of the gate (no warm-up), cold nighttime temps in CO and NM, need to be through NM before snow begins in fall, can be less social/more solitary, the southern terminus isn’t as epic as the northern one (still exciting though)

Flip-flop—A “flip-flop” hike is a good option for hikers who wish to avoid as much snow travel as possible. There are multiple flip-flop options. The Continental Divide Trail Coalition’s CDT planning guide does an excellent job of explaining the most popular flip-flop methods.

Picking a start date

In a normal snow year, NOBOs start mid-April through mid-May. The goal is to get through Southern New Mexico while temps aren’t unbearably hot and to arrive at the Colorado border just as the snowpack becomes more manageable. NOBO hikers will generally want to reach the Canadian border by late September before snow starts to blanket the Northern Rockies.

SOBOs start later—mid-June to early July—since they’ll have to wait for the snowpack to melt in Glacier National Park and the high mountain passes of Montana. They generally want to be through the San Pedro Parks in New Mexico by November.

Permits

There’s no long-distance permit to thru-hike the CDT, but you’ll need to obtain some permits for certain areas along the way. We recommend trying to reserve an itinerary in advance ahead and then planning on visiting one of the backcountry permit stations to make changes or fill in any gaps. Planning ahead helps, but walk-up permits are usually easy to obtain. The Continental Divide Trail Coalition’s free CDT planning guide gives all the contact info and details, but we’ll outline the basics:

- National Parks — You’ll need permits to camp in Glacier, Yellowstone, and Rocky Mountain National Park, and this process can be frustrating, especially if you are attached to a particular itinerary and timeline. Some parks require bear cans, restrict mileage between backcountry campsites, and often have area closures for maintenance, wildlife migrations, spawning(and the associated bear activity), or because a bear has become accustomed to campsite food/waste and needs to be removed. Be prepared to be flexible with your entry dates and campsite itineraries. Here are the few ways thru-hikers have been able to book backcountry sites in the national parks:

- Early Access Lottery Periods: Some thru-hikers will try to book some or all of their backcountry campsites through the NPS lottery systems via recreation.gov. Applications open in March and, if you win, you will be notified a day and time slot to log into recreation.gov and book an itinerary. While the lottery system reduces the number of users competing for a site simultaneously during the early access period, you are still in a pool of other recreators making a mad dash for available sites. Plan out your preferred itinerary prior to logging in, and be ready with several itinerary alternatives. We suggest you study the booking page, know the names of the zones the campsites are in, the name of the campsite (most have an abbreviation on the booking site), know where it is on the map, and which other sites are nearby as a quick alternative. That way, in case your first choice is already reserved, you’ll know how to quickly pivot to the next option.

- Advanced Reservations: Around the end of April or the beginning of May, these national parks open their booking system to the general public. This is first come, first serve, and just like with the lottery, be ready with lots of options. If you don’t get what you were looking for, rangers suggest regularly checking back because reservations are often canceled (especially a few days before the trip).

- Walk-ups: Many thru-hikers have some sites booked ahead and then head to a permit office to fill in the blanks. Others avoid the online system altogether and head to the permit stations to make a plan from there. If you do plan to go to a permit office, we suggest going well before the office opens (there will be a line during the high season) to get first dibs on walk-up permits. With millions of visitors every year, the NPS is doing its best to have a fair and functional permit system via recreation.gov, but in our experience, going to the ranger station first thing the day or two before you plan to enter the park and talking to a ranger who knows the up-to-date status on the trails and campsites is the most pleasant way to book. You just might not camp where you thought you would.

- Blackfeet Reservation — You need a Blackfeet Nation recreation permit to thru-hike on the Blackfeet Reservation.

- Indian Peaks Wilderness — The CDT skirts the boundary of this wilderness area, only entering it for a few miles. You only need a permit if you plan to camp in this area, and you can get one from the US Forest Service Indian Peaks Wilderness page.

- Wilderness Self-Service Permits — Some wilderness areas have kiosks where you can obtain a required self-issue permit for free.

Familiarize yourself with LNT

With the growing popularity of long-distance trail hiking, it’s crucial to minimize your environmental impact while trekking through the outdoors. Being in pristine wilderness is a privilege and thru-hikers who familiarize themselves with and follow the Leave No Trace Principles (LNT) will be able to travel through these amazing places without degrading it. For a detailed guide on these principles for backpackers, watch our video on LNT.

Budgeting

Budgeting is absolutely essential and can be quite challenging; many hikers have to cut their trips short because their funds run dry. On the CDT, the average thru-hiker spends about $2-$3 per mile (between $5,000 and $8,000) on expenses like motel rooms, food, drinks, and replacing gear. If you have a lot of gear to purchase or update, this can set you back anywhere from $0 to over $5,000 (more on this below in the packing list).

If you are looking for ways to thru-hike without breaking the bank, check out our article, 21 Tips for Backpacking On a Budget.

Putting your regular life on hold

While some thru-hikers feel more like their truest selves on the trail, walking away from “regular life” for five or six months is still a big and challenging undertaking. If this is your first thru-hike, you might find it helpful to check out our Quick Guide to Thru-Hiking the PCT or Quick Guide to Thru-Hiking the AT, which go into more detail about the following tasks you’ll need to do:

- Quit your job/take a leave of absence

- Autopay your bills

- Make arrangements for pets

Physical prep

Unless you’re already spending 8-12 hours walking up and down uneven terrain, there really isn’t a close in-town equivalent to get you physically up to speed for hiking the CDT. However, that is not to say training doesn’t support your mental and physical fitness for thru-hiking. It is a good idea to get your body used to this kind of wear and tear as well as figure out what support you might need to function optimally. Many people find that by starting slow and not overloading their packs, their bodies get used to the conditions on the trail once they get started, especially for the NOBOs, where the terrain difficulty builds gradually. If you’re SOBO, you’ll probably want to get a little prep in before your start date. Check out our guide, How to Train for Hiking & Backpacking Trips for some great tips to get your body primed for a CDT thru-hike.

Safety

While the idea of thru-hiking can raise an eyebrow from your loved ones who picture it as a big risk, you are typically safer than if you were in a big city. Nonetheless, preparation and awareness of potential dangers are essential to bring you and your loved ones peace of mind. Here are some risks to familiarize yourself with before you begin your thru-hike:

- Giardia

- Dehydration

- Exposure (heat exhaustion/stroke and hypothermia)

- Overuse injuries

- Rattlesnake bites

- Grizzly bear attacks

- Avalanches

- Drowning; sketchy river crossings

- Lightning strikes

Make a rough itinerary

Map out your mileage goals, water supply targets, emergency exit routes, rest day locations, and resupply points before hitting the trail. This approach serves multiple purposes: it helps familiarize yourself with the trail, establish a completion goal, streamline logistics, and provide a detailed itinerary to share with your support network. We found that involving friends and family in the planning stages was greatly appreciated, offering them peace of mind and a sense of connection to your adventure.

Consider carrying a personal locator beacon (PLB)

Personal Locator Beacons (PLBs) provide crucial emergency support during your hike. In case of injury or perilous situations where exiting the area is needed ASAP, you can call for help instantly. Many PLBs also offer real-time tracking, allowing your loved ones to follow your journey remotely – which is pretty neat. We highly recommend the Garmin InReach Mini 2 for its advanced satellite technology, built-in mapping, and two-way messaging capabilities. For those on a tighter budget, the Spot Gen4, while with fewer features, is a safe bet.

Wildlife

The CDT offers ample opportunities for wildlife encounters, most of which are thrilling and positive experiences. You’re likely to frequently spot deer, elk, bears, and wild turkeys along your journey. With a bit of luck, you might even catch sight of mountain goats, moose, or wolves – truly special moments on the trail.

Rattlesnakes

You probably already know that rattlesnakes are venomous. It is true that they’re abundant on certain parts of the CDT. It’s good to have a healthy respect for rattlers, but like most wildlife, the chances of a dangerous encounter are very slim. Stay aware of your footing and surroundings, scan the trail in front of you, and you’ll be able to forewarn any rattlers that might be close. If you do scare a snake, stay calm and back away slowly. Snakes usually move out of the way once you give them some space. If a snake doesn’t move, bushwhack around it, giving it plenty of room. If you still have questions, check out our video on snake & cougar safety for more info.

Rodents

Mice, chipmunks, and squirrels will visit you along the entirety of the Continental Divide Trail. It is a major “ick” to be awoken by the nibbling, scuffling sounds of these opportunists, or even worse, to wake up in the morning and find your precious food is contaminated. They’ll chew through tents, packs, stuff sacks, and even chow down on the sweat-salted cork of your trekking poles. Mice also carry disease and can be problematic near human-made structures like cabins and picnic shelters. Be sure to store your food properly so you can avoid rodent rage along the way.

Bears

Bears are ever-present on the Continental Divide Trail. You’ll only encounter black bears on the southern half of the CDT, which pose little threat to humans. Grizzly bear country roughly spans from Wyoming to Canada. These bears can be dangerous if they feel threatened and extra precautions should be taken when hiking in their territory. Grizzlies don’t want to interact with you, but it is usually when they are surprised or separated(sow and her cub) that a grizzly will act aggressively out of fear. Make noise while you hike, especially in high brush where they can’t see you coming, and if you are hiking into the wind (they usually catch your scent well before you head into their territory). Even better, if you can arrange it, walk with someone or in a small group. When you have a hiking partner or two, you tend to make enough noise to give ample warning of your presence. The most important thing you can do to protect yourself (and ultimately, the bears) is to carry bear spray and have the ability to hang your food. Check out our article on facts and myths of bear encounters for more info. You might also like our article, Does Bear Spray Really Work?

Moose

Moose can be seen foraging along the trail from Colorado north. If you notice signs of beaver habitat, you’re probably also in moose country. Moose are massive, powerful animals. They’re not aggressive, but they’ll charge if they feel threatened. Do not approach moose. If a moose is blocking the trail (which they do frequently), go around it, giving it a wide berth. If a moose chases you, hide behind a tree or other large object. They have a hard time figuring out how to get around.

Resupplying

Resupplying on the Continental Divide Trail is usually a mash-up of shopping along the way and mailing boxes of food and supplies to themselves. We’ll go over the main pros and cons of each strategy below, but generally, we recommend shopping in bigger towns and sending boxes to more remote locations. Because there are so many variables in route planning, resupply isn’t as straightforward for the CDT as it is for other long trails. We won’t go into full detail here, but Yogi’s Continental Divide Trail Handbook is a popular resource for planning CDT resupply. There’s also a free online tool for printing CDT mailing labels for resupply boxes.

MAIL DROPS

Pros: More enjoyment and satisfaction of creating your own trail food, greater variety and potential for healthier options, better accommodation of specific dietary needs or restrictions, reduced time and stress spent on resupply in trail towns, a chance to involve friends or family in your adventure through meal prep

Cons: Mail drops take a lot of pre-hike time and planning, you have to work through the logistics of tracking drops/coordinating with local post office schedules, shipping is expensive, might be stuck with food you can’t stand anymore, too much food to carry or you didn’t mail enough

GROCERY SHOPS

Pros: If you daydream about food while hiking, it is really nice to shop for exactly what you want when you’re craving it, supports local communities along the trail, avoids shipping costs, no help needed (better option for international hikers)

Cons: Food options can be limited or poor quality (gas stations and dollar stores), more work/stress in trail towns, can be expensive in certain places, lots of packaging and excess packaging/food to get rid of

Some hikers don’t prepare anything ahead of time. Instead, they shop in the towns with the best stores and send boxes ahead to themselves wherever needed.

We recommend sending mail drops to these places since shopping opportunities are limited or non-existent:

- Pie Town, NM

- Ghost Ranch, NM

- Doc Campbell’s, NM

- Leadore, ID (Bannock Pass)

- South Pass City or Atlantic City, WY (right next to each other)

- Lima, MT

- Encampment, WY (Battle Pass)

- East Glacier Village, MT

- Twin Lakes, CO

- Old Faithful Village, WY (Yellowstone)

- Brooks Lake Lodge, WY

- Benchmark Wilderness Ranch, MT

Gear List

Make sure to check out our Ultimate Backpacking Checklist so you don’t forget something important.

Below you’ll find our current favorite backpacking gear. If you want to see additional options, our curated gear guides are the result of many years of extensive research and hands-on testing by our team of outdoor experts.

BACKPACK

- Best Backpacking Pack Overall: REI Flash 55 – Men’s / REI Flash 55 – Women’s

- Best Ultralight Backpacking Backpack: Hyperlite Mountain Gear Unbound 40

- More: Check out our best backpacking backpacks guide for ultralight and trekking options

TENT

- Best Backpacking Tent Overall: Big Agnes Copper Spur HV UL2

- Best Ultralight Tent: Zpacks Duplex

- Best Budget Tent: REI Half Dome SL 2+

- Best Tent Stakes Overall: All One Tech Aluminum Stakes

- More: Check out our best backpacking tents guide for more options

SLEEPING BAG/QUILT

- Best Sleeping Bag Overall: Men’s Feathered Friends Swallow YF 20 / Women’s Feathered Friends Egret YF 20

- Best Quilt Overall: Enlightened Equipment Revelation 20

- More: Check out our best backpacking sleeping bags guide and best backpacking quilts guide for more options

SLEEPING PAD

- Best Sleeping Pad Overall: NEMO Tensor All-Season

- Best Foam Sleeping Pad: NEMO Switchback

- More: Check out our best backpacking sleeping pads guide for ultralight and trekking options

CAMP KITCHEN

- Best Backpacking Stove Overall: MSR PocketRocket 2

- Best Backpacking Cookware Overall: TOAKS Titanium 750ml

- Best Backpacking Coffee Overall: Starbucks VIA

- More: Check out our best backpacking stoves guide and best backpacking cookware guide for ultralight and large group options

WATER & FILTRATION

- Best Water Filter Overall: Sawyer Squeeze

- Best Hydration Bladder Overall: Gregory 3D Hydro

- Best Backpacking Water Bottles: Smartwater Bottles

- More: Check out our best backpacking water filters guide and best backpacking water bottles guide for ultralight and large group options

CLOTHING

- Best Hiking Pants Overall: Men’s Outdoor Research Ferrosi / Women’s The North Face Aphrodite 2.0

- Best Hiking Shorts Overall: Men’s Patagonia Quandary / Women’s Outdoor Research Ferrosi

- Best Women’s Hiking Leggings: Fjallraven Abisko Trekking Tights HD

- Best Rain Jacket Overall: Men’s Patagonia Torrentshell 3L / Women’s Patagonia Torrentshell 3L

- Best Rain Pants: Men’s Patagonia Torrentshell 3L / Women’s Patagonia Torrentshell 3L

- Best Down Jacket Overall: Men’s Patagonia Down Sweater Hoodie / Women’s Patagonia Down Sweater Hoodie

- Best Fleece Jacket Overall: Men’s Patagonia Better Sweater / Women’s Patagonia Better Sweater

- Best Sunshirt Overall: Men’s Outdoor Research Echo / Women’s Outdoor Research Echo

- Best Socks Overall: Men’s Darn Tough Light Hiker Micro Crew / Women’s Darn Tough Light Hiker Micro Crew

- Beste Ultralight Liner Glove: Patagonia Capilene Midweight Liner

- More: Check out our best backpacking apparel lists for more options

FOOTWEAR & TRACTION

- Best Hiking Shoes Overall: Men’s HOKA Speedgoat 6 / Women’s HOKA Speedgoat 6

- Best Hiking Boots Overall: Men’s Salomon X Ultra 4 GTX / Women’s Lowa Renegade GTX

- Best Hiking Sandals Overall: Men’s Chaco Z/1 Classic / Women’s Chaco Z/1 Classic

- Best Camp Shoes Overall: Crocs Classic Clogs

- Best Traction Device for Hiking Overall: Kahtoola MICROspikes

- More: Check out our best backpacking footwear lists for more options

NAVIGATION

- Best GPS Watch Overall: Garmin Instinct 2 Solar

- Best Personal Locator Beacon (PLB): Garmin inReach Mini 2

- More: Check out our article How to Use Your Phone as a GPS Device for Backpacking & Hiking to learn more

FOOD

FIRST-AID & TOOLS

- Best First-Aid Kit Overall: Adventure Medical Kits Ultralight/Watertight .7

- Best Pocket Knife Overall: Kershaw Leek

- Best Multitool Overall: Leatherman Wave+

- Best Headlamp Overall: Black Diamond Spot 400-R

- Best Power Bank Overall: Nitcore NB 10000 Gen 3

- More: Check out our best first-aid Kit guide, best pocket knife guide, best multitool guide, best backpacking headlamps guide, and best power banks guide for more options

MISCELLANEOUS

- Best Trekking Poles Overall: Black Diamond Pursuit

- Best Backpacking Chair Overall: REI Flexlite Air

- Best Backpacking Stuff Sack Overall: Hyperlite Mountain Gear Drawstring

- More: Check out our best trekking poles guide, best backpacking chairs guide, and best stuff sacks guide for more options

CDT Regions Quick Facts

The CDT is divided into 4 sections. It travels through a multitude of diverse landscapes, weather, and challenges. Below, we’ll outline a handful of fun facts about each section.

Need a visual? Follow along with this CDNST interactive map.

New Mexico – 820 miles

- New Mexico, the “Land of Enchantment”, is full of rich Native American, Hispanic, and Western culture

- The Southern New Mexican desert is arid but full of intriguing plants (sage, ocotillo, prickly pear, cholla, datura, and piñon pine) and animals (lizards, snakes, cows, coyote, and wild horses)

- Daytime temps can reach over 100℉, while nighttime temps can be below freezing

- Pie Town was settled during the Dust Bowl as a pit stop for travelers to grab a slice of pie. Decades later, the Pie-O-Neer pie shop keeps the tradition alive

- The CDT crosses an expansive lava flow, El Malpais, and shares a path with the old Zuni-Acoma trade route

- Mount Taylor is visible from up to 100 miles away

Colorado – 740 miles

- A lot of the CDT in Colorado stays high and follows the peaks and ridges of the physical Continental Divide, where the trail offers constant incredible views of alpine meadows, moraine lakes, seas of mountains, and valleys below

- Altitude sickness (AMS) can be problematic for some in this area

- NOBOs will have to contend with afternoon thunderstorms and lightning

- The CDT passes numerous derelict cabins, historic ghost towns, and mining operations

- Grays Peak (14,270 ft.) is the highest point not only along the CDT

- Before entering WY, the Trail loops through Rocky Mountain National Park and the awe-inspiring Zirkels in the Medicine Bow and Routt National Forests

Wyoming – 500 miles

- The CDT crosses the Great Divide Basin, a vast flat area where water doesn’t drain to any ocean

- There are some very long dry stretches and road walks in WY

- The craggy Wind River Range and Teton Wilderness are natural wonders and highlights of the CDT

- The Green River at the south end of the Wind River Range roughly marks the boundary of grizzly bear country

- The CDT coincides with the Oregon Trail wagon route and passes through South Pass City, a well-preserved pioneer town that serves as a museum

- The Trail passes through Yellowstone National Park, a true geological wonder of the world and wildlife haven

Montana & Idaho – 1,030 miles

- The CDT edges along the Idaho-Montana border through the Beaverhead-Deerlodge National Forest and into the Bitterroot Range, where it intersects the Nez Perce Trail

- The CDT covers about 110 miles of ground in Glacier National Park, where grizzly bears and mountain goats roam among the incredibly steep mountains and rock monoliths

- After traversing some of the most remote country Glacier has to offer, the CDT heads down the Waterton Valley River to the northern terminus and Canadian border at Goat Haunt

Get Involved

The CDT truly is an amazing footpath, and it took a monumental effort to turn it from a dream into a reality. Every year, the Continental Divide Trail Coalition, Continental Divide Trail Society, and US Forest Service work hard to maintain and protect the trail for recreation. Here are a few ways you can help and get involved:

Thru-hiking the CDT is a big challenge with big rewards, and we hope this guide helps you plan a successful hike.